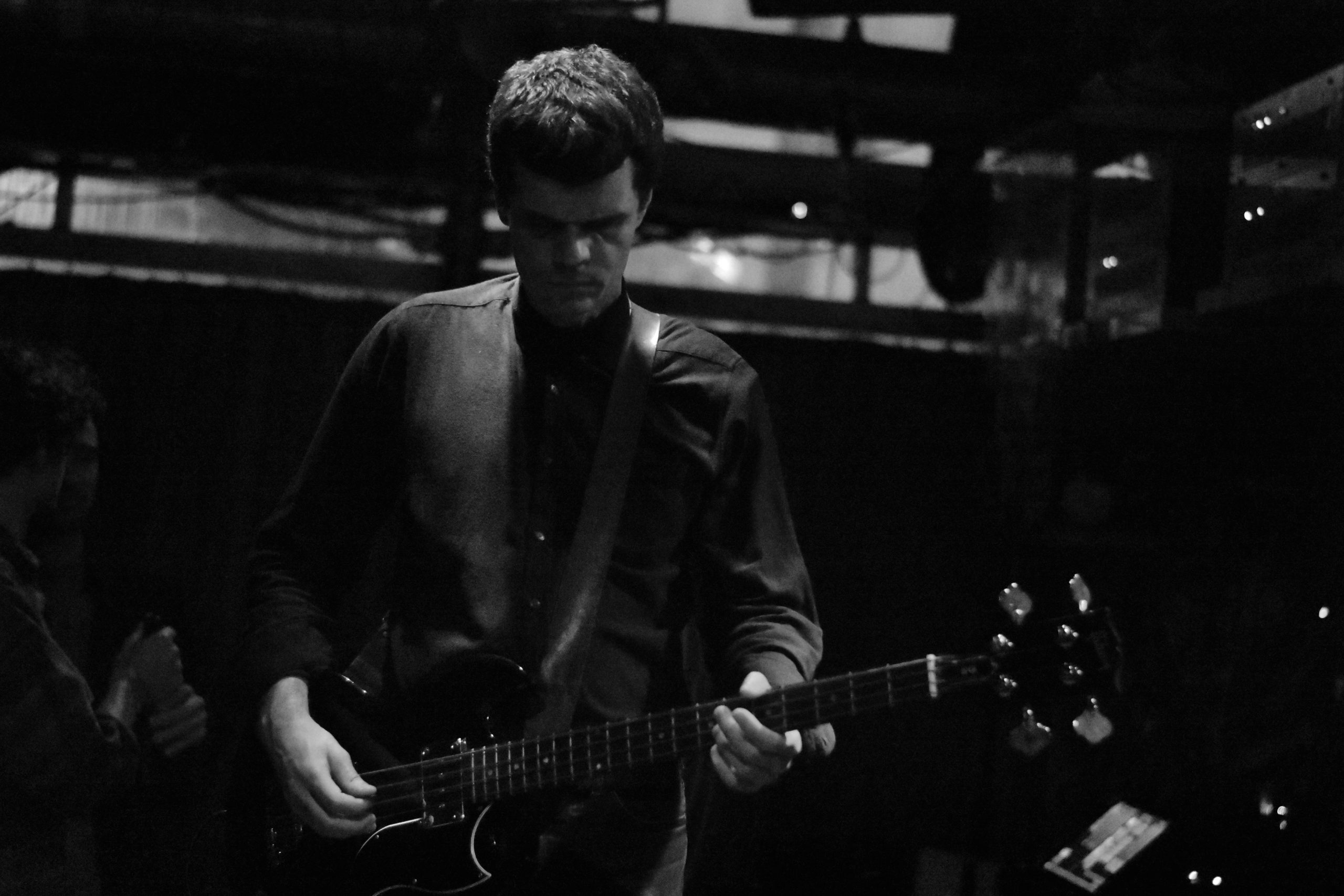

Desde las profundidades de Portugal, los promotores locales Dazed and Confused trajeron a 10 000 Russos a Viena, quienes dieron una memorable presentación en el rhiz. Pero antes de que el trío de experimentados músicos nos dieran una lección sobre profundidad musical, wolfgang se dio a la tarea de platicar con ellos sobre sus orígenes, filosofía y por qué el rock está muerto.

English translation below

¿Cómo empezaron a tocar juntos? Porque los géneros en los que se enfocan no son muy populares, entonces debe ser difícil encontrar a gente que quiera tocar eso.

JOAO PIMENTA: Fue natural. Primero Pedro y yo en los inicios, después André ha entrado 2 años después, por ahí. E inició precisamente con batería y guitarra; André ha entrado para el bajo y nos conocíamos de conciertos. No nos conocíamos como amigos de infancia que empezaron una banda juntos, porque somos de distintos sitios; no hemos crecido en los mismos sitios. Y no había un plan, ha sido algo natural, como hacer música un rato y ahí estamos ahora, hablando aquí (ríe).

ANDRÉ COUTO: (ríe)

¿Cuáles fueron sus orígenes musicales?

JP: Son muy diferentes. No tenemos una relación musical con lo pasado o lo presente. Nosotros cuando hacemos música no estamos pensando…a veces suena a algo que conocemos o la música se parece a la de alguna banda, no sé, pero no es intencional, por lo menos no de mi parte. No pienso en influencias o así. Lo que hacemos queremos que suene como nuestra banda, no sonar a esto o aquello. Claro que se puede poner en un contexto…¿Qué estoy diciendo? Estoy hablando muy mal español. Ya voy a empezar a hablar inglés (risas) Es como una peli que ha cambiado los subtítulos (risas). Sí, pero no sé muy bien cómo responder a eso.

¿Dirían que hay una intención política en su música?

PEDRO PESTANA: Intención reflexiva, tal vez, en ese sentido. Y tal vez en algunas posiciones pero es un poco difícil porque a veces tenemos posiciones diferentes.

AC: Todo es político–

PP: Todo es político.

AC: Pero no hay nada intencional.

¿Cómo es su proceso usual para escribir música? ¿Es a través de la improvisación, un poco como el jazz?

PP: Un poco, la fuente siempre es ésa.

AC: El improvisar.

¿Cuál dirían ustedes que es el atractivo de la repetición en la música?

PP: Un montón de cosas. Por un lado, los juegos que puedes hacer; con la repetición puedes salir de las medidas, de lo que es…aquí es muy métrico la verdad, pero hay montón de cosas con las que puedes jugar dentro de ese marco. Y otra cosa que está pasando con la gente es que cada vez está escuchando sonidos más cortos y más rápidos. También eso me da la sensación que está pasando por todos lados. No sé, en el underground y todo, los sonidos que escuchas que tienen las canciones son todos más cortos, más rápidos. Pero tiene que ver un poco con esa noción de ritmo.

AC: Pero también –no sé cómo ven eso–, la repetición y el minimalismo te permiten más libertad. Cuando la música no es repetitiva, es direccional. Estás diciéndole a alguien que está oyendo „va por aquí“; estás apuntándole un camino, estamos dirigiendo para oír. Cuando las cosas son repetitivas, tú mismo haces tu camino dentro de la música, porque algo tan monótono como la repetición tiene esa hipnosis, ese lado de trance.

PP: Sí, y todas las dinámicas que hacen y que tienen que ver con intención, se perciben. Te topas con que uno está subiendo o bajando, te vas con él, y la cosa navega un poco por ahí. Pero no sólo está ese juego „arriba, abajo“; hay muchas más cosas qué hacer. Pero también es sugestivo, sobre todo en la creación, como decía él; tiene que ver con estar ahí „hanging“, „colgado“ (risas). Y después descubres las cosas interesantes de esa aparente ausencia de salida.

¿Cómo es la escena underground en su país de origen?

PP: Bueno, es un país de 10 millones de personas. De calidad está muy bien; tienes gente ahí que está haciendo cosas interesantes.

AC: Somos un país muy creativo en todas las áreas; en toda cosa que sea de creatividad, de crear cosas. Más la escena underground es el propio país. Es un país underground (risas) no hay escena underground. Somos muy pocos.

PP: Claro que hay cosas más mainstream y que pasan en la radio y todo eso. Pero en general el underground donde nos movemos al menos está con muy buena gente haciendo cosas, la verdad. Pero si tocas sólo en Portugal, no consigues vivir de esto por ejemplo, al menos a este nivel, aunque depende. No puedes vivir de esto si sólo tocas en círculos underground porque tampoco es tan grande.

¿Dirían que todavía hay lugares a los cuáles llegar con la música, incluso cuando actualmente se dice que el rock está muerto?

PP: El rock es reaccionario. Yo veo al rock como algo muy reaccionario, muy white trash. Lo que era revolucionario hace 50 años es muy reaccionario ahora, no sirve.

¿Y aún hay camino para experimentar en la música o ya todo está hecho?

AC: Todo está hecho y desde hace más de 70 años. Pero lo importante es tomar otro camino y cambiar esas cosas que ya están, reciclarlas (risas). Porque ya todo está hecho.

PP: Sí, pero todavía queda mucho para hacer en campos musicales y también en lo que hablabas hace rato; el campo político. También ahí.

OK, muchas gracias. Ustedes tienen la última palabra.

JP: Es la primera vez que tocamos aquí en Austria. Había tocado aquí 3 años atrás en un sitio llamado AU, ¿no sé si lo conozcas? Digo, no sé si siga abierto (risas). Hace 3 ó 4 años. Y hemos viajado mucho; en la noche tenemos que ir a otro país. Por ejemplo, esta noche tocamos en Viena y mañana en Linz, luego vamos a tocar a un festival también. Pienso que nos va a ir bien.

P: Enjoy the music!

ENGLISH TRANSLATION

From the depths of Portugal, local promoters Dazed and Confused brought 10 000 Russos to Vienna, who gave a memorable performance at the rhiz. However, and before the trio of experimented musicians gave us a lesson in musical depth, wolfgang took the chance to talk with them about their origins, philosophy and why Rock is dead.

How did you start playing together? The genres you focus on aren’t all that popular, so it must be hard to find people who want to play them.

JOAO PIMENTA: It was very natural. At the beginning it was Pedro and me. Then André joined in 2 years later. And it started with just the guitar and the drums. André joined with the bass and we knew each other from concerts. We were never childhood friends that started a band together because we grew up in different places. And there was never a plan; it all started very naturally, like getting together to make some music and here we are now, talking (laughs).

ANDRÉ COUTO: (laughs)

What were your musical origins?

JP: They’re very different. We don’t have a direct musical relationship with the past or the present. When we’re making music, we’re not thinking. It sometimes sounds like something we know or even a bit like a band, but it’s never intentional, at least not on my part. I don’t think about influences or anything like that. What we do, we want it to sound like our own band, not like “this or that”, but of course it can be contextualised. What am I saying? I’m speaking really bad Spanish, I should start speaking English (laughs). It’s like a movie in which you have changed the subtitles (laughs). But yeah, I don’t know how to properly answer that.

Would you say there’s political intent in your music?

PEDRO PESTANA: A reflective intent, rather. Maybe in some stances but it’s a little difficult because we all have different points of view.

AC: Everything is political.

PP: Everything is political.

AC: But it’s nothing intentional.

What kind of process do you go through for making music? Is it through improvisation, like Jazz?

PP: A little bit. The source is always that.

AC: To jam.

Which would you say is the appeal of repetition?

PP: Plenty of things. On one hand, the puzzles you can come up with. With repetition, you can distance yourself from metric, of what is…everything is very metric to be honest, but there are plenty of things you can play with within those ranges. Something else that is happening is that people are more and more gravitating towards shorter and faster sounds. I get the feeling that’s happening everywhere. I don’t know, even in the underground scene, the sounds that you can hear in songs are tighter, faster. But it has a bit to do with that notion of rhythm.

AC: But also –and I don’t know how you see it– repetition and minimalism allow more freedom. When music is not repetitive, it is directional. You’re telling the listener “it’s this way”; you’re pointing out a way, you’re directing the hearing. When things are repetitive, you make your own way inside the music, because something so monotonous as repetition has this quality of hypnosis, of trance.

PP: Yes, and all the dynamics that have to do with intention are also perceived. One can be going up and down, you follow through and things navigate like that. But this “up and down” scheme is not the only one; there’s s so much more to do. But it’s also suggestive, especially in creation, as he was saying. It has to do with being there, hanging (laughs). And that’s where you find the interesting things in that seeming “no way out”.

How’s the underground scene in your home country?

PP: Well, it’s a 10-million-inhabitants country. The quality is really good, you have people doing very interesting things.

AC: We’re a very creative country in all fronts; anything that has to do with creativity and creating things. And the underground scene is the country itself. It’s an underground country (laughs). There’s no underground scene, we’re too few.

PP: Of course, there are more mainstream things that are played on the radio and whatnot. But at least the underground scene in which we move has very good people doing things, honestly. Although for example, if you only play in Portugal, you can’t make a living out of this, or if you only play in the underground circles, because they’re not that big.

Would you say there are still “places to go” to with music? Even when it’s been said that Rock is dead?

PP: Rock is very reactionary. I see Rock as something very reactionary, very white trash. What was revolutionary 50 years ago, nowadays is quite reactionary, it doesn’t work.

And is there still room for experimenting in music or is everything already been done?

AC: Everything’s been done for more than 70 years already. What’s important is to take another path and change those things, to recycle them (laughs). Because it is all been done.

PP: Yeah, but there’s still a lot to be done in the music realm as well as what you were mentioning before, in politics. There too.

Thank you! You have the last word.

JP: It’s the first time we play together in Austria. I had played here in a place called AU, I don’t know if you know it. I mean, I don’t know if it’s still even open (laughs). It was about three or four years ago. And we’ve been travelling around, and we keep moving between countries. Tonight, for example, we play in Vienna and tomorrow in Linz, then we’re playing at a festival, too. But I think we’ll do good.

PP: Enjoy the music!

Political Sciences BA and Mexican-born expat, trying their best to hold onto their filmmaking dreams. I turn to music and films when existence becomes unbearable